Venezuela: A Brief Historical Lesson

From Simón Bolívar's liberation struggles to the modern Bolivarian Republic—and its surprising Greek connection

On the occasion of the U.S. intervention in Venezuela, I believe it’s useful to learn some interesting historical facts about the country and its connections to the French and Greek Revolutions.

First, it’s important to mention a U.S. president of that era, whom we briefly discussed last summer in my article on U.S. Independence Day and the Greek Revolution.

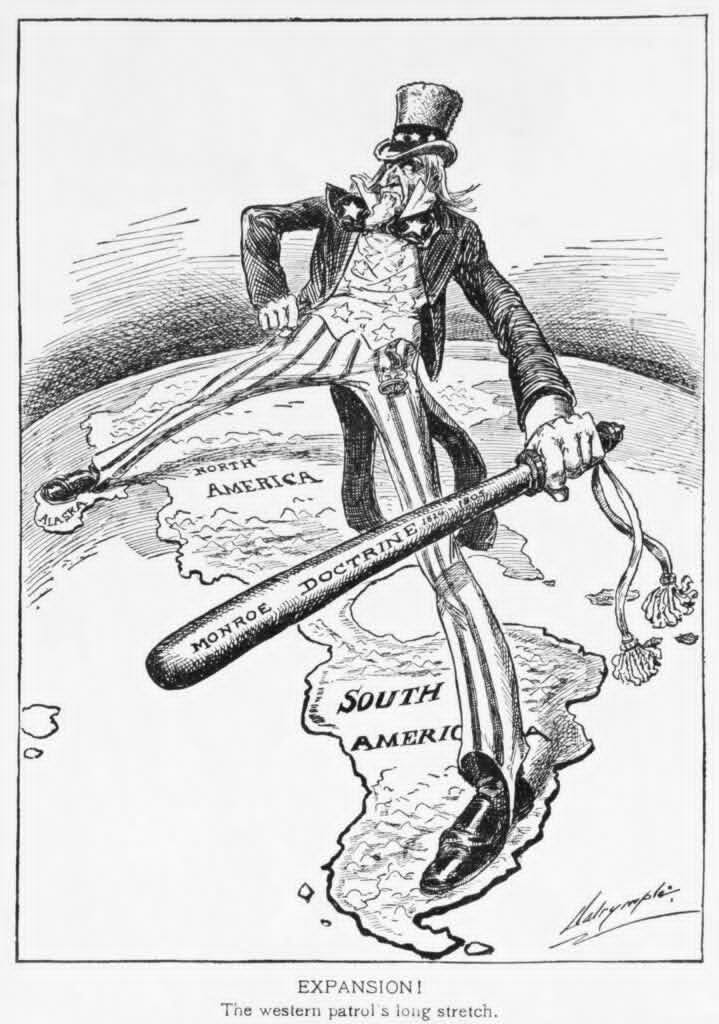

As we noted the day before yesterday, even before President Trump mentioned it and renamed it the “Donroe Doctrine”, the Monroe Doctrine, announced by U.S. President James Monroe in 1823, warned European powers against new colonization or interference in the Western Hemisphere. It declared the Americas closed to future European colonies, while the U.S. pledged non-interference in European affairs or existing colonies. Any such intervention would be viewed as a hostile act against the U.S.

The essence of this doctrine was that Europeans should stay away from Latin America, as this region falls entirely and exclusively within the U.S. sphere of influence, shaping American foreign policy for the years to come.

It was the era following the French Revolution, which expressed, among other things, the principle of individual self-determination as well as that of peoples. After two decades of wars and Napoleon’s defeat, the victorious Great European Powers had decided at the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to restore the Old monarchical Regimes, balance their mutual powers, and mutual support through the establishment of the Holy Alliance against any revolutions that broke out.

That same year, however, with the end of the American-British War (1812-1815) and the Treaty of Ghent, the independence of the United States—won 40 years earlier—was confirmed, and Serbia became the first region of the Ottoman Empire to gain autonomy. It was clear that while the Old Regimes had won the Napoleonic Wars, the tide had turned—there was no going back. Peoples, inspired by the principles of the French Revolution, would spend the next 100 years trying to win independence from the multi-ethnic empires they were part of and/or demand more rights from their once-absolute monarchs.

Thus, by 1830, national-liberation or liberal revolutions inspired by nationalism and constitutional ideology erupted in several countries: In Spain in 1820, the liberal military uprising was ultimately crushed by French troops in 1823; in Italy, the Carbonari revolution of 1820 was suppressed by Austrian troops in 1821, during the same period that the Greeks were revolting against the Ottomans. A few years later (1830), the Poles revolted against the Russians and the Belgians against the Dutch union, with the former failing and the latter winning independence (the Greeks, meanwhile, had already gained autonomy and would win full independence shortly thereafter).

This was indeed the Age of Revolutions, as the British historian Eric Hobsbawm aptly put it.

And what does Venezuela have to do with all this, and why is its official name the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela?

After the Spanish colonies in the Americas had recently revolted successfully, consequently depriving Spain of an essential source of revenue, the Spanish King sought to reclaim them.

In January 1820, soldiers assembled at Cádiz for an expedition to South America, angry over infrequent pay, bad food, and poor quarters, mutinied and pledged fealty to the 1812 liberal Constitution that the King refused to accept. Three years of liberal rule (the “Trienio Liberal”) followed and ultimately the King requested help against the liberal revolutionaries which led to the Congress of Verona authorizing France to intervene.

But what about the Spanish colonies?

Enter, Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar Palacios Ponte y Blanco (1783–1830), known simply as Simón Bolívar. He is known by the nickname El Libertador (The Liberator), and as the George Washington of South America for his leadership role in the aforementioned independence movements, just as Washington led the United States to independence. As a leader in the struggle for independence in the regions that today constitute Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia, he is considered a significant hero in these countries, as well as in the rest of Spanish-speaking America.

Behind the paywall: What happened to Bolivar’s ambitious plan to create a large confederation of American states—and what role did the U.S. play? What kind of country is Venezuela today and what does Greece have to do with Bolivar?