In the year 200 BC

"The great new Hellenic world"

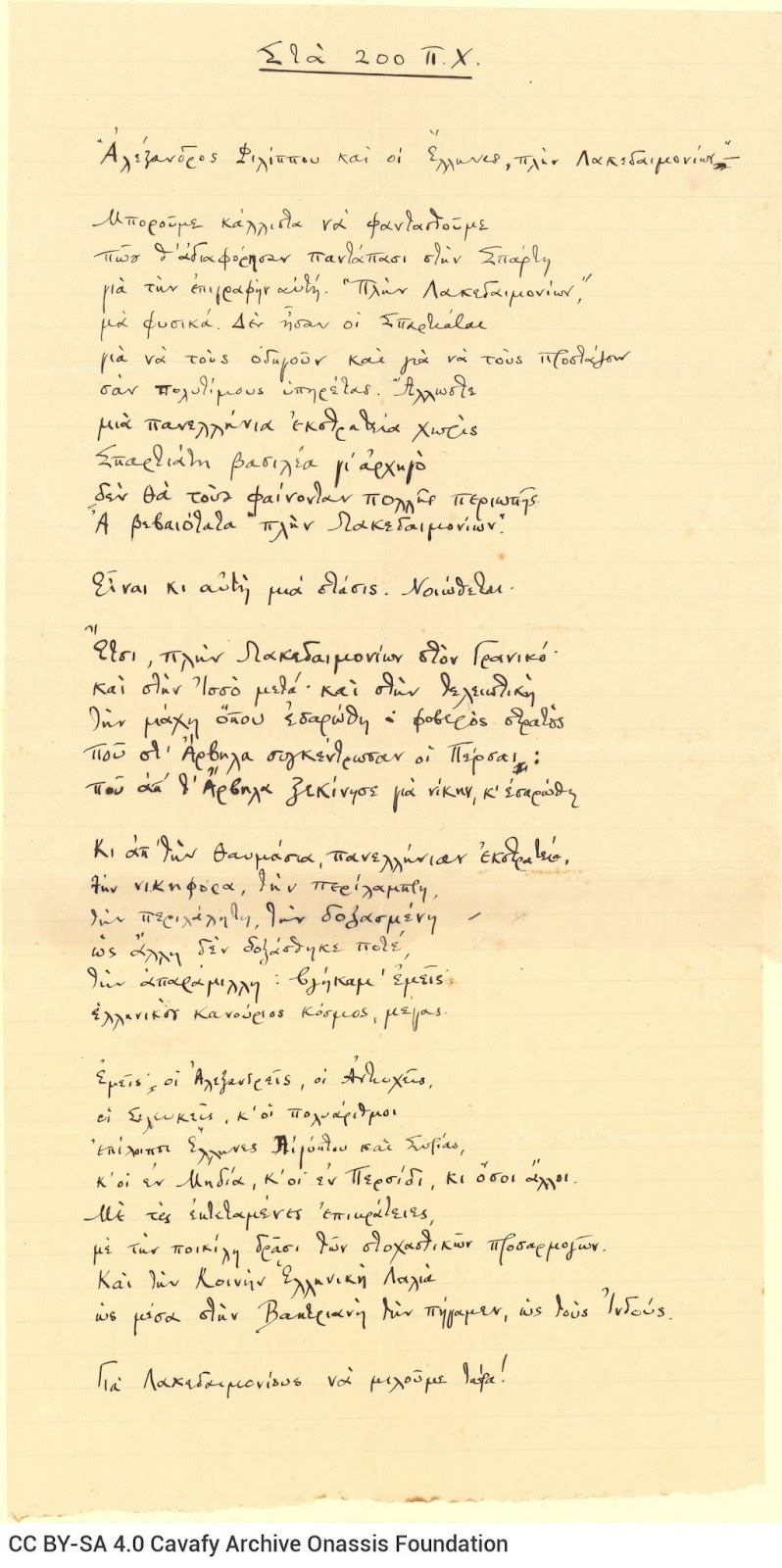

*ακολουθεί κείμενο στα ελληνικά

The following is an assignment for the course Classical History II in the Department of History & Archaeology at the University of Athens, under the instruction of Professor Mrs Aneziri. It examines the history of the Hellenistic period. Essentially, the essay constitutes a summary of what has been said so far during the current semester under the guise of a commentary on the poem “In the year 200 BC” by C.P. Cavafy:

“Alexander, son of Philip, and the Greeks except the Lacedaimonians...”

We can very well imagine

how completely indifferent the Spartans would have been

to this inscription. “Except the Lacedaimonians”—

naturally. The Spartans

weren’t to be led and ordered around

like precious servants. Besides,

a pan-Hellenic expedition without

a Spartan king in command

was not to be taken very seriously.

Of course, then, “except the Lacedaimonians.”

That’s certainly one point of view. Quite understandable.

So, “except the Lacedaimonians” at Granikos,

then at Issus, then in the decisive battle

where the terrible army

the Persians mustered at Arbela was wiped out:

it set out for victory from Arbela, and was wiped out.

And from this marvelous pan-Hellenic expedition,

triumphant, brilliant in every way,

celebrated on all sides, glorified

as no other has ever been glorified,

incomparable, we emerged:

the great new Hellenic world.

We the Alexandrians, the Antiochians,

the Selefkians, and the countless

other Greeks of Egypt and Syria,

and those in Media, and Persia, and all the rest:

with our far-flung supremacy,

our flexible policy of judicious integration,

and our Common Greek Language

which we carried as far as Bactria, as far as the Indians.

Talk about Lacedaimonians after that!

In the Year 200 B.C. | Reprinted from C.P. CAVAFY: Collected Poems Revised Edition, translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard, edited by George Savidis.When, during one of our recent lectures, we were presented with the map titled "Macedonia and the Aegean World in 200 BC", I couldn’t help but recall the penultimate poem by Konstantinos Cavafy. In this work, the Great Alexandrian masterfully extols Alexander the Great and his achievements, which so effectively continued the work of his father, Philip II. Truly, an entire semester’s material could not have been summarized more succinctly in just a few lines.

In the poem, the anonymous narrator evaluates Alexander’s achievements from the perspective of a Greek living in 200 BCE—the year the Second Macedonian War began. This conflict saw the Romans, spurred by the Rhodians and Attalids, ultimately defeat the Macedonian forces of Philip V at Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE. Rome would emerge as the arbiter of Greek affairs, and its subsequent clashes with the Seleucids and ultimately the Ptolemies would cement its status as a world power.

However, before this occurred, the remarkable achievements of Alexander, his Successors (Diadochi), and their descendants (Epigoni) took place—achievements the anonymous narrator describes with admiration: the dissemination and evolution of Greek culture within the newly forged multicultural world, and the advancement of sciences and arts, which left a legacy that profoundly influenced both the ancient and subsequent worlds.

All of this—except the Lacedaimonians (Spartans), who refused to participate in the Panhellenic campaign, justifying their stance by claiming they would not break Spartan tradition or follow others in a military expedition, believing themselves superior warriors. The narrator critiques this ironically: the Spartans’ refusal, which Alexander respected, appears in hindsight as shortsightedness and an inability to adapt to the changes brought by the Macedonian king’s vision. Their isolationism, provincialism, localism, and lack of grand ambition became a recipe for failure across the ages—factors that ultimately contributed to Greek subjugation under Rome.

Cavafy, writing from multicultural Alexandria just years after the disastrus Asia Minor Campaign (1922)—a catastrophe royalists exacerbated by rejecting Venizelos’s far-sighted vision—understood this historical pattern all too well.

Regardless, 2,256 years ago, Alexander sent the 300 panoplies—spoils from the Battle of the Granicus River—to Athens rather than his own homeland and capital, Pella. He dedicated them to Athena, aiming to emphasize the Panhellenic character of his campaign. Through this act, he sought to clarify that, despite his personal ambitions, the expedition embodied a collective Greek aspiration and his vision for a new world—one that left no room for narrow-mindedness or parochial thinking. And this point needed to be underscored.

That’s certainly one point of view. Quite understandable. Yet, Alexander’s Successors demonstrated the same pragmatic tolerance toward the parochial mindset of mainland Greek cities, primarily because they, like Alexander himself, had far more important matters to attend to. For instance, Diodorus records that in 314 BCE,

Antigonus introduced a decree declaring Cassander an enemy unless he submitted to Antigonus, who had been appointed general and assumed control of the kingdom. The same decree proclaimed all cities “free”—autonomous and without garrisons. Diodorus further notes that Ptolemy, upon learning of Antigonus’s pro-Greek-freedom resolutions, issued a similar declaration that year, aiming to convince the Greeks that their autonomy concerned him as much as it did Antigonus.

Thus, while the Successors overflowed with such “understanding,” these proclamations were ultimately hollow, serving merely as tools to win over city-states in their struggle to consolidate power.

However, in the back of their minds, they harbored something entirely different from mere tolerance. Fully embracing Alexander’s vision of creating a new world, they pursued either holistic policies—like Antigonus and Demetrius, who sought to restore the empire’s entirety—or fragmented strategies, as seen with Ptolemy and Philetaerus, who consolidated regional kingdoms. To legitimize their rule, at first they cultivated ties to Alexander and the Argead dynasty, asserting to their subjects a connection (however tenuous) to the original Macedonian royal house.

Moreover, all successor dynasties meticulously showcased their personal achievements or familial harmony through epithets like Soter ("Savior"), Poliorketes ("Besieger"), Nikator ("Victor"), Kallinikos ("Gloriously Triumphant"), Philopator ("Father-Loving"), and Philadelphos ("Sibling-Loving"), binding their ascent and tenure to these idealized virtues.

And so, from this marvelous pan-Hellenic expedition, triumphant, brilliant in every way, celebrated on all sides, glorified as no other has ever been glorified, incomparable, emerged a new Greek world after decades of conflict. Ultimately, four successor dynasties solidified:

The Antigonids, with their capital at Pella;

The Attalids, ruling from Pergamon;

The Lagids/Ptolemies, centered in Alexandria of Egypt, with its "wide streets, magnificent temples, and public spaces" as Strabo described;

The Seleucids, who initially established their capital at Seleucia before relocating to Antioch.

It is worth noting, however, that the dynasties of the Epigoni—the descendants of Alexander’s Successors—were fully consolidated only in 238 BCE, when Attalus I, the adopted son of Eumenes I, dared to assume the title of king after his decisive victory over the Gauls in Asia Minor. For the remaining Epigoni, though they claimed kingship far earlier than Attalus, it took decades after Alexander’s death to formally adopt the royal title, often under pressure from advisors and kin.

These dynasties gradually cultivated claims of divine ancestry: the Ptolemies linked their lineage to Dionysus, the Seleucids to Apollo, the Antigonids to Zeus and Heracles, and the Attalids to Zeus and Athena. The Seleucids and Ptolemies also institutionalized the worship of Alexander the Great alongside their own, carefully avoiding disruption of local religious practices. This pragmatic approach stemmed from their hybrid kingdoms, which retained the core of Macedonian monarchy while assimilating Persian (for the Seleucids) and Egyptian (for the Ptolemies) traditions.

Temples in Egypt, Asia Minor, and Syria functioned as states within states—autonomous, economically self-sufficient, and controlling vast lands. Neither Alexander nor his successors dared antagonize these institutions, recognizing them as vital bridges to local populations. In Egypt, for instance, Greeks constituted a mere 1/70th of the population, explaining why Macedonian kings (as Pharaohs) prioritized alliances with priestly elites. The situation in the Seleucid Empire—the most geographically distant and ethnically fragmented realm—was even more precarious. Its subjects included Greeks of varied origins (merchants, mercenaries) and non-Greek groups like Phoenicians, Syrians, Bactrians, and Indians, making religious and cultural diplomacy essential to stability.

By contrast, the kingdoms of the Attalids and particularly the Antigonids were more "Greek" and demographically homogeneous. While the Attalids’ core territory was not the historic Macedonian heartland (unlike the Antigonids), their proximity to mainland Greece drove them to bolster their dynasty’s prestige by patronizing sanctuaries and cities across Greece and Asia Minor.

The Antigonids, meanwhile, positioned themselves as the historical and ideological successors of the Argeads, establishing a form of national monarchy. Their rule emphasized continuity with the Argead legacy, leveraging Macedonian identity to unify their realm.

Another key practice adopted by the Hellenistic monarchies, continuing Alexander’s policies, was the systematic foundation of cities bearing dynastic names in regions they sought to control, such as Seleucia, Antioch, Cassandreia, Apamea, and Laodicea. Equally significant was their adherence to interdynastic marriages—following Alexander’s strategy of forging kinship bonds with rival dynasties. Despite near-constant warfare between Hellenistic kingdoms (adhering to the maxim "the enemy of my enemy is my friend"), they periodically formed coalitions of convenience against common foes, ratified through royal marriages.

Finally, further developing Alexander’s policies and always acting in the name of his grand vision—which they made sure to proclaim in every possible way—the Hellenistic kingdoms compensated for the absence of a traditional aristocracy (especially in realms far from mainland Greece) by establishing courts composed of “Friends of the King.” These were individuals of diverse backgrounds, usually immigrants from the Greek mainland, who served in administrative and cultural roles.

Such was the case with the companions of Lysimachus, as described by Diodorus, who urged him to save himself by any means necessary. However, he replied that it would be dishonorable to look after his own safety by abandoning his army and friends, ultimately losing his life at the Battle of Corupedium in 281 BCE.

We, says the poet—quite logically including himself among the Greeks who emerged from the work of Alexander and his successors. We, the Alexandrians, the Antiocheans, the Seleucians, and the numerous other Greeks of Egypt and Syria, those in Media, in Persia, and all the rest. The Alexandrian poet recognizes in Alexander the figure of a national leader, the creator of the marvelous Greek world that expanded and flourished to an unprecedented degree thanks to the policy of the Macedonian king and his successors, who approached the peoples they conquered as liberators rather than oppressors

Greek cities, as mentioned, were founded through deliberate policy across all the Hellenistic kingdoms, creating vast territories with our flexible policy of judicious integration. This included the establishment of Gymnasiums, the introduction of worship of new gods, characterized by the syncretism of Greek and Eastern traditions—such as the worship of Sarapis—and the blending of different legal systems, exemplified by the creation of the Koinodikion in Egypt. A vivid example is a preserved letter in which Eumenes II responds favorably to a city that sent him a three-member delegation—one of whom was a Gaul—requesting the right to establish a Gymnasium, adopt Greek laws, and organize their civic life according to Greek models.

Lastly, through the fertile blending of Greek religion with local deities and the spread of Greek education, Alexander and his successors, carried our Koine (Common) Greek Language as far as Bactria, as far as the Indians. They laid robust foundations for the adoption and preservation of Greek cultural elements, offering local populations the opportunity to perceive themselves as citizens of the new kingdoms while embracing the marvel of Hellenic civilization.

Talk about Lacedaimonians after that!

Bonus video: Sean Connery recites the poem Ithaca, perhaps the most famous poem of C.P. Cavafy. It is obviously inspired by Homer’s Odyssey. I literally felt goosepumps the first time I heard Sir Connery riciting this. To be honest, I still do:

Ithaka

By C. P. Cavafy

As you set out for Ithaka hope your road is a long one, full of adventure, full of discovery. Laistrygonians, Cyclops, angry Poseidon—don’t be afraid of them: you’ll never find things like that on your way as long as you keep your thoughts raised high, as long as a rare excitement stirs your spirit and your body. Laistrygonians, Cyclops, wild Poseidon—you won’t encounter them unless you bring them along inside your soul, unless your soul sets them up in front of you. Hope your road is a long one. May there be many summer mornings when, with what pleasure, what joy, you enter harbors you’re seeing for the first time; may you stop at Phoenician trading stations to buy fine things, mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony, sensual perfume of every kind— as many sensual perfumes as you can; and may you visit many Egyptian cities to learn and go on learning from their scholars. Keep Ithaka always in your mind. Arriving there is what you’re destined for. But don’t hurry the journey at all. Better if it lasts for years, so you’re old by the time you reach the island, wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way, not expecting Ithaka to make you rich. Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey. Without her you wouldn't have set out. She has nothing left to give you now. And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you. Wise as you will have become, so full of experience, you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

Source: C.P. Cavafy: Collected Poems (Princeton University Press, 1975). Translated by Edmund Keeley and Philip Sherrard.

Read also about the poem God abandons Antony by Cavafy, the poem that inspired Leonard Coen to write one of his most beautiful songs:

*ακολουθεί κείμενο στα ελληνικά

(το παρακάτω κείμενο αποτελεί εργασία για το μάθημα Κλασική Ιστορία Β΄ στο Τμήμα Ιστορίας & Αρχαιολογίας του ΕΚΠΑ, με καθηγήτρια την κα. Ανεζίρη, το οποίο πραγματεύεται την ιστορία της ελληνιστικής περιόδου. Ουσιαστικά η εργασία αποτελεί μία περίληψη όσων έχουν ειπωθεί μέχρι τώρα στο εξάμηνο υπό τον μανδύα του σχολιασμού του ποίηματος του Κ.Π. Καβάφη.)

«Aλέξανδρος Φιλίππου και οι Έλληνες πλην Λακεδαιμονίων—»

Μπορούμε κάλλιστα να φαντασθούμε

πως θ’ αδιαφόρησαν παντάπασι στην Σπάρτη

για την επιγραφήν αυτή. «Πλην Λακεδαιμονίων»,

μα φυσικά. Δεν ήσαν οι Σπαρτιάται

για να τους οδηγούν και για να τους προστάζουν

σαν πολυτίμους υπηρέτας. Άλλωστε

μια πανελλήνια εκστρατεία χωρίς

Σπαρτιάτη βασιλέα γι’ αρχηγό

δεν θα τους φαίνονταν πολλής περιωπής.

A βεβαιότατα «πλην Λακεδαιμονίων».

Είναι κι αυτή μια στάσις. Νοιώθεται.

Έτσι, πλην Λακεδαιμονίων στον Γρανικό·

και στην Ισσό μετά· και στην τελειωτική

την μάχη, όπου εσαρώθη ο φοβερός στρατός

που στ’ Άρβηλα συγκέντρωσαν οι Πέρσαι:

που απ’ τ’ Άρβηλα ξεκίνησε για νίκην, κ’ εσαρώθη.

Κι απ’ την θαυμάσια πανελλήνιαν εκστρατεία,

την νικηφόρα, την περίλαμπρη,

την περιλάλητη, την δοξασμένη

ως άλλη δεν δοξάσθηκε καμιά,

την απαράμιλλη: βγήκαμ’ εμείς·

ελληνικός καινούριος κόσμος, μέγας.

Εμείς· οι Aλεξανδρείς, οι Aντιοχείς,

οι Σελευκείς, κ’ οι πολυάριθμοι

επίλοιποι Έλληνες Aιγύπτου και Συρίας,

κ’ οι εν Μηδία, κ’ οι εν Περσίδι, κι όσοι άλλοι.

Με τες εκτεταμένες επικράτειες,

με την ποικίλη δράσι των στοχαστικών προσαρμογών.

Και την Κοινήν Ελληνική Λαλιά

ώς μέσα στην Βακτριανή την πήγαμεν, ώς τους Ινδούς.

Για Λακεδαιμονίους να μιλούμε τώρα!

Κωνσταντίνος Π. Καβάφης: Στα 200 π.Χ.

Επιμέλεια Γ. Π. Σαββίδη. Τα Ποιήματα, Τ. Β’ 1919 - 1933, Ίκαρος 1963

Όταν σε ένα από τα τελευταία μας μαθήματα, μας παρουσιάστηκε ο χάρτης με τίτλο “Η Μακεδονία και ο κόσμος του Αιγαίου στα 200 π.Χ.”, δεν μπόρεσα να μην φέρω στο νου μου το πρότελευταίο ποίημα του Κωνσταντίνου Καβάφη. Σ’ αυτό, ο Μεγάλος Αλεξανδρινός επαινεί αριστουργηματικά τον Μεγάλο Αλέξανδρο και τα κατορθώματά του, που με τόση αποτελεσματικότητα συνέχισε το έργο του πατέρα του, Φιλίππου Β΄ και πραγματικά δεν θα μπορούσε να συνοψιστεί καλύτερα η ύλη ενός ολόκληρου εξαμήνου σε λίγες μόνο αράδες.

Στο ποίημα ο ανώνυμος αφηγητής αξιολογεί όσα πέτυχε ο Αλέξανδρος, από την οπτική ενός Έλληνα που ζει στα 200 π.Χ., το έτος δηλαδή που ξεκίνησε ο Β΄ Μακεδονικός Πόλεμος, με τους Ρωμαίους υποκινούμενοι από τους Ροδίτες και τους Ατταλίδες, να κατανικούν τελικά τα μακεδονικά στρατεύματα του Φιλίππου Ε΄ στις Κυνός Κεφαλές το 197. Η Ρώμη θα γίνει ρυθμιστής των ελληνικών πραγμάτων και η σύγκρουση αρχικά με τους Σελευκίδες και τελικά με τους Πτολεμαίους, θα την αναδείξει σε κοσμοκράτειρα.

Όμως μέχρι να συμβεί αυτό, έλαβαν χώρα τα εντυπωσιακά επιτεύγματα του Αλεξάνδρου, των Διαδόχων και των Επιγόνων, τα οποία ο ανώνυμος αφηγητής περιγράφει με θαυμασμό: η διάδοση και εξέλιξη του ελληνικού πολιτισμού, μέσα στον νέο, πολυπολιτισμικό κόσμο που είχε δημιουργηθεί και η πρόοδος των επιστημών και των τεχνών, που άφησε μια κληρονομιά που επηρέασε βαθιά τον αρχαίο και τον μεταγενέστερο κόσμο.

Όλα αυτά, πλην Σπαρτιατών, που αρνήθηκαν να συμμετάσχουν στην πανελλήνια προσπάθεια, με τη δικαιολογία ότι δεν ήθελαν να σπάσουν την Σπαρτιατική παράδοση και να μην ηγούνται μιας πολεμικής εκστρατείας, γιατί θεωρούσαν ότι ήταν οι καλύτεροι πολεμιστές. Αυτό σχολιάζεται ειρωνικά από τον αφηγητή, καθώς η άρνηση των Σπαρτιατών που έγινε σεβαστή από τον Αλέξανδρο, όταν εξετάζεται υπό το πρίσμα της συνολικής επιτυχίας των Ελλήνων μοιάζει περισσότερο με έλλειψη διορατικότητας από πλευράς Σπαρτιατών και με αδυναμία αποδοχής των αλλαγών που έφερνε η δράση του μεγάλου Μακεδόνα. Ο απομονωτισμός, ο επαρχιωτισμός, ο τοπικισμός και η έλλειψη ενός μεγάλου οράματος των Ελλαδιτών, ήταν αυτό που συνετέλεσε τελικά στο να κατακτηθούν από τους Ρωμαίους και είναι μία συνταγή αποτυχίας ανά τους αιώνες. Αυτό φυσικά το γνωρίζει ο Κωνσταντίνος Καβάφης, ζώντας στην πολυπολιτισμική Αλεξάνδρεια και γράφοντας το ποίημα λίγα μόλις χρόνια μετά το πέρας της Μικρασιατικής Εκστρατείας, την οποία οι βασιλικοί καταδίκασαν σε Καταστροφή, με το μένος τους απέναντι στον Βενιζέλο και τη μη υιοθέτηση του μακρόπνοου οράματός του.

Όπως και να έχει, 2.256 χρόνια πριν, ο Αλέξανδρος έστειλε στην Αθήνα και όχι στην ιδιαίτερη πατρίδα του και πρωτεύουσά του Πέλλα, 300 πανοπλίες από τα λάφυρα μετά τη μάχη στον Γρανικό ποταμό, αφιερώνοντάς τες στην Αθηνά, θέλοντας έτσι να τονίσει τον πανελλήνιο χαρακτήρα της εκστρατείας του. Επιθυμούσε μ’ αυτόν τον τρόπο να καταστεί σαφές, ότι ανεξάρτητα από τις προσωπικές του φιλοδοξίες, η εκστρατεία αυτή εξέφραζε μια πανεθνική επιθυμία και το όραμά του για τον νέο κόσμο. Σ’ αυτόν τον κόσμο δεν χωρούσαν ξεροκέφαλοι και μικρόνοες. Και ήταν ανάγκη να τονιστεί αυτό.

Ήταν βέβαια κι αυτή των Σπαρτιατών μια στάσις. Νοιώθεται. Και οι διάδοχοι του Αλέξανδρου επέδειξαν την ίδια κατανόηση με αυτόν στην τοπικιστική νοοτροπία των πόλεων της μητροπολιτικής Ελλάδας, πιο πολύ γιατί είχαν πολύ σημαντικότερα πράγματα να ασχοληθούν, ακριβώς όπως ο Αλέξανδρος. Παραδείγματος χάριν, ο Διόδωρος αναφέρει ότι το 314 π.Χ., ο Αντίγονος εισήγαγε ψήφισμα σύμφωνα με το οποίο ο Κάσσανδρος ανακηρυσσόταν εχθρός αν δεν πειθαρχούσε στον ίδιο που είχε αναδειχθεί στρατηγός και είχε πάρει στα χέρια του τον έλεγχο του βασιλείου. Με το ίδιο ψήφισμα ανακηρυσσόταν όλες οι πόλεις ελεύθερες, δίχως φρουρές και αυτόνομες. Ξανά ο Διόδωρος, αναφέρει πως το ίδιο έτος, ο Πτολεμαίος, όταν πληροφορήθηκε τις αποφάσεις που ψήφισαν οι Μακεδόνες με τον Αντίγονο αναφορικά με την ελευθερία των Ελλήνων, κυκλοφόρησε και ο ίδιος παρόμοια διακήρυξη, επειδή επιθυμούσε να πληροφορηθούν οι Έλληνες ότι η αυτονομία τους απασχολούσε και τον ίδιο εξίσου με τον Αντίγονο. Βλέπουμε λοιπόν ότι οι διάδοχοι… “ξεχειλίζουν¨ από κατανόηση, όμως πρακτικά αυτές οι διακηρύξεις αποτελούσαν κενό γράμμα και μία προσπάθειά τους να προσεταιριστούν τις πόλεις-κράτη, στον αγώνα τους να εδραιώσουν την εξουσία τους.

Στο πίσω μέρος του μυαλού τους όμως, είχαν κάτι τελείως διαφορετικό από την κατανόηση. Υιοθετώντας πλήρως το όραμα του Αλέξανδρου για τη δημιουργία ενός νέου κόσμου, είτε ακολούθησαν ολιστική πολιτική προσπαθώντας να αποκαταστήσουν το σύνολο της αυτοκρατορίας του όπως ο Αντίγονος και ο Δημήτριος, είτε μεριστική προσπαθώντας να εδραιωθούν σε τοπικά βασίλεια όπως ο Πτολεμαίος και ο Φιλέταιρος. Προκειμένου να το πετύχουν αυτό, αρχικά ανέπτυξαν δεσμούς με τον Αλέξανδρο και τον οίκο των Αργεαδών, προκειμένου να ισχυρίζονται στους υπηκόους τους ότι συνδέονται με τον μακεδονικό βασιλικό οίκο, με τον έναν ή τον άλλον τρόπο. Επιπλέον, όλες οι διάδοχες δυναστείες, φρόντισαν να επιδεικνύουν τα προσωπικά κατορθώματά ή/και την οικογενειακή γαλήνη τους οίκου τους, με προσωνύμια όπως Σωτήρ, Πολιορκητής, Νικάτωρ, Καλλίνικος, Φιλοπάτωρ και Φιλάδελφος, συνδέοντας την άνοδο και την παραμονή τους στο θρόνο με αυτά.

Κι απ’ την θαυμάσια πανελλήνιαν εκστρατεία λοιπόν, που ως άλλη δεν δοξάσθηκε καμία και μετά από διαμάχες δεκαετιών, βγήκε ένας ελληνικός καινούργιος κόσμος, μέγας και 4 τελικά διάδοχες δυναστείες: οι Αντιγονίδες με πρωτεύουσα την Πέλλα, οι Ατταλίδες με πρωτεύουσα την Πέργαμο, οι Λαγίδες ή Πτολεμαίοι με πρωτεύουσα την Αλεξάνδρεια την εν Αιγύπτω με “τους φαρδείς δρόμους, τα ωραιότατα τεμένη και δημόσιους χώρους” κατά τον Στράβωνα, και οι Σελευκίδες με πρωτεύουσα αρχικά τη Σελεύκεια και κατόπιν την Αντιόχεια. Αξίζει να σημειωθεί πάντως, πως οι δυναστείες των επιγόνων, των απογόνων των διαδόχων δηλαδή του Αλέξανδρου, παγιώθηκαν τελικά μόλις το 238, όταν ο θετός γιος του Ευμένη Α’, Άτταλος Α’, τολμά να πάρει τον τίτλο του βασιλιά, μετά από τη μεγάλη νίκη του κατά των Γαλατών. Και στους υπόλοιπους επίγονους βέβαια, αν και πολύ νωρίτερα από τον Άτταλο, τους πήρε αρκετές δεκαετίες μετά το θάνατο του Μ. Αλεξάνδρου να αποτολμήσουν να ονομαστούν βασιλείς, συνήθως μάλιστα μετά από παραινέσεις Φίλων και συγγενών

Οι δυναστείες αυτές, καλλιέργησαν σταδιακά τη θεϊκή καταγωγή τους: οι Πτολεμαίοι συνέδεσαν τη δυναστεία τους με τον Διόνυσο, οι Σελευκίδες με τον Απόλλωνα, οι Αντιγονίδες με τον Δία και τον Ηρακλή και οι Ατταλίδες με τον Δία και την Αθηνά. Οι Σελευκίδες και οι Πτολεμαίοι, καθιέρωσαν επίσης τη λατρεία του Μεγάλου Αλεξάνδρου, μαζί με των ιδίων, χωρίς να διαταράξουν παράλληλα τις όποιες τοπικές θρησκευτικές πρακτικές, σοφά πράττοντας, καθώς τα βασίλειά τους αποτελούσαν υβριδικά μορφώματα, με πυρήνα μεν τα χαρακτηριστικά της μακεδονικής μοναρχίας, μεγάλο μέρος της κληρονομιάς τους όμως ήταν περσική και αιγυπτιακή αντίστοιχα. Τα Ιερά άλλωστε σε Αίγυπτο, Μ. Ασία και Συρία ειδικά, αποτελούσαν κράτος εν κράτει. Ήταν αυτόνομα, με δικές τους εκτάσεις και οικονομική ευμάρεια. Πέραν της δύναμής τους λοιπόν, δεν θέλησε ούτε ο Αλέξανδρος, ούτε οι διάδοχοί του να διαταράξουν τις σχέσεις τους με αυτά, καθώς αποτελούσαν διαχρονικά τη γέφυρά τους με τον ντόπιο πληθυσμό. Και όταν οι Έλληνες ανεξάρτητα καταγωγής, αποτελούσαν σύμφωνα με μελέτες στην Αίγυπτο για παράδειγμα μόλις το 1/70 του πληθυσμού, γίνεται κατανοητό το γιατί οι Μακεδόνες Βασιλείς/Φαραώ επιθυμούσαν να τα έχουν καλά με τα τοπικά ιερατεία. Η κατάσταση, δεν θα πρέπει να ήταν καλύτερη στην επικράτεια των Σελευκιδών, την πιο μακρινή συγκριτικά με τη μητροπολιτική Ελλάδα και με την πιο ανομοιογενή σύνθεση υπηκόων, όχι μόνο των Ελλήνων κάθε καταγωγής που έσπευσαν να μεταναστεύσουν στα βάθη της Ανατολής, είτε ως έμποροι, είτε ως μισθοφόροι στρατιώτες, αλλά και των ακόμα πιο ετερογενών μη Ελλήνων, από τους Φοίνικες και τους Σύρους, μέχρι τους Βάκτρους και τους Ινδούς.

Αντίθετα, τα βασίλεια των Ατταλιδών και ιδιαίτερα αυτό των Αντιγονιδών, ήταν πιο “ελληνικά” και πιο ομοιογενή πληθυσμιακά. Ο πυρήνας της επικράτειας των Ατταλιδών, μπορεί να μην ήταν το ιστορικό βασίλειο της Μακεδονίας όπως των Αντιγονιδών , αλλά λόγω εγγύτητας με τον Ελλαδικό χώρο, προσπάθησαν να ενισχύσουν τη φήμη του οίκου τους ευεργετώντας ιερά και πόλεις σε Ελλάδα και Μ. Ασία. Οι δε Αντιγονίδες, εμφανίζονταν σαν μια ιστορική και ιδεολογική συνέχεια των Αργεαδών και εγκαθίδρυσαν τρόπον τινά μία εθνική μοναρχία.

Μία ακόμη πρακτική στην οποία επιδόθηκαν οι ελληνιστικές μοναρχίες, συνεχίζοντας την πολιτική του Αλέξανδρου, ήταν η προγραμματική ίδρυση πόλεων με δυναστικές ονομασίες στις περιοχές που επιθυμούσαν να εδραιώσουν την κυριαρχία τους, όπως Σελεύκεια, Αντιόχεια, Κασσάνδρεια, Απάμεια και Λαοδίκεια. Ενδιαφέρον επίσης έχει η συνέχιση των επιγαμιών, της πρακτικής του Αλέξανδρου για τη δημιουργία δεσμών συγγένειας με άλλες δυναστείες. Πράγματι, παρά το γεγονός ότι πρακτικά τα ελληνιστικά βασίλεια δεν σταμάτησαν να πολεμούν ποτέ μεταξύ τους, τηρώντας το “ο εχθρός του εχθρού μου είναι φίλος μου”, σύναπταν κατά καιρούς τις λεγόμενες συμμαχίες προθύμων προκειμένου να πλήξουν έναν κοινό εχθρό, τις οποίες επικύρωναν με γάμους μελών τους.

Τέλος, εξελίσσοντας την πολιτική του Αλέξανδρου και πάντα λειτουργώντας στο όνομά του μεγάλου οράματός του, κάτι που φρόντιζαν να διατυμπανίζουν παντοιοτρόπως, υποκατέστησαν την έλλειψη αριστοκρατίας -ειδικά τα βασίλεια μακριά από την μητροπολιτική Ελλάδα- συγκροτώντας αυλές με “Φίλους του Βασιλέα”, που ήταν άνθρωποι διαφορετικής καταγωγής, συνήθως μετανάστες από τον μητροπολιτικό ελλαδικό χώρο, οι οποίες είχαν διοικητικό και πολιτιστικό χαρακτήρα. Τέτοιοι ήταν και οι φίλοι του Λυσιμάχου κατά τον Διόδωρο, που τον πίεσαν με τις συμβουλές τους να σώσει τον εαυτό του με οποιονδήποτε τρόπο, όμως εκείνος τους αποκρίθηκε ότι δεν ήταν καθόλου τιμητικό να φροντίσει για τον εαυτό του εγκαταλείποντας τον στρατό και τους φίλους του, για να χάσει τελικά τη ζωή του στη μάχη του Κουροπεδίου το 281 π.Χ.

Εμείς, λέει ο ποιητής, εντάσσοντας πολύ λογικά και τον εαυτό του στους Έλληνες που προέκυψαν μέσα από το έργο του Αλεξάνδρου και των διαδόχων του. Εμείς, οι Αλεξανδρείς, οι Αντιοχείς, οι Σελευκείς, κ’ οι πολυάριθμοι επίλοιποι Έλληνες Αιγύπτου και Συρίας, κ’ οι εν Μηδία, κ’ οι εν Περσίδι, κι όσοι άλλοι. Ο αλεξανδρινός ποιητής αναγνωρίζει στο πρόσωπο του Αλέξανδρου τον εθνάρχη, τον δημιουργό του θαυμάσιου ελληνικού κόσμου που απλώθηκε και αναπτύχθηκε σε πρωτόγνωρο βαθμό χάρη στην τακτική του Μακεδόνα βασιλιά και των διαδόχων του να προσεγγίσουν τους λαούς που κατέκτησαν ως απελευθερωτές και όχι ως κατακτητές.

Ελληνικές πόλεις όπως είπαμε δημιουργήθηκαν κατόπιν στοχευμένης πολιτικής σε όλα τα ελληνιστικά βασίλεια, δημιουργώντας τες εκτεταμένες επικράτειες, με την ποικίλη δράσι των στοχαστικών προσαρμογών. Αυτή η δράση περιλάμβανε δημιουργία Γυμνασίων, εισαγωγή νέων λατρείων που χαρακτηρίζονταν από τον συγκρητισμό του ελληνικού με τους ανατολικούς πολιτισμούς όπως αυτή του Σάραπι και το συνταίριασμα πολλών διαφορετικών δικαίων, με τη δημιουργία για παράδειγμα στην Αίγυπτο του Κοινοδικίου. Ένα χαρακτηριστικό παράδειγμα είναι μία επιστολή που διασώζεται, στην οποία ο Ευμένης Β΄ απαντά θετικά σε πόλη που του απέστειλε μία τριμελή επιτροπή -με το ένα μέλος της μάλιστα να είναι Γαλάτης- ζητώντας του να αποκτήσουν γυμνάσιο, νόμους και πολιτειακή οργάνωση κατά τα ελληνικά πρότυπα.

Με το γόνιμο ανακάτεμα της ελληνικής θρησκείας με τις ντόπιες θεότητες, καθώς και με τη διάδοση της ελληνικής παιδείας ο Αλέξανδρος και οι διάδοχοί του κατόρθωσαν να πάνε την Κοινήν Ελληνική Λαλιά ως μέσα στην Βακτριανή, ως μέχρι και τους Ινδούς. Έθεσαν έτσι ισχυρά θεμέλια για την υιοθέτηση και διατήρηση στοιχείων του ελληνικού πολιτισμού και πρόσφεραν την ευκαιρία στους ντόπιους να θεωρήσουν εαυτούς πολίτες των νέων βασιλείων, γνωρίζοντας το θαύμα του ελληνικού πολιτισμού.

Για Λακεδαιμονίους να μιλούμε τώρα!

Διαβάστε επίσης το άρθρο σχετικά με το Απολείπειν ο Θεόν Αντώνιον, το ποίημα του Καβάφη που ενέπνευσε τον Leonard Coen να γράψει ένα από τα ομορφότερα τραγούδια του: